Debo at 100; memories of my boss, mentor and friend.

31 March 2020

I am writing this on the centenary of the birth of Deborah Mitford, Duchess of Devonshire, affectionally known as Debo. For more than half a century, Chatsworth in Derbyshire was the central purpose and creative joy of Debo’s life, for which she proved to be a supreme ‘house keeper’ of her husband’s ancestral estate, and which owes a good deal of its present, radiant good health to her.

But in the aristocratic world of primogeniture, she once said, with all the focus on the male line of descent, ‘Women are lower than the belly of a snake’. I was lucky enough to work for her, and become friends with her over two decades, and I saw up close how far from the truth this was; her fearless spirit, wit and charm, alongside her sharp commercial acumen and curiosity, indeed her whole Mitfordian force of nature, were fundamental in re-imagining Chatsworth for the modern age, in partnership with her husband Andrew, the 11th Duke of Devonshire (1920-2004). When Andrew died in 2004, one of my colleagues wrote, so aptly, ‘Truly the Duke and Duchess were virtuosos, and Chatsworth was their instrument’.

But Debo’s gag about the belly of a snake has a sharp sting to it nonetheless; even someone who was extensively written about, who wrote so much about her own life, in books and letters, and who contributed one way or another to the mythologizing of her sisterhood over the decades, owed much of her status and indeed the focus of her life’s work, to her husband’s title and family inheritance. Her particular contribution, so dependent as it was on her quality of human connection and the power of her personality, rather than a job title or formal training, is easy to dismiss and hard to capture in the history books. It is sad, even if inevitable, to observe how quickly the sands of time blur and fade the impact her life force had on Chatsworth and on the many thousands of people who encountered her in the flesh. So while she remains fresh in my mind, as one of the most extraordinary people I have ever met, here are some photographs and the memories they spark for me. They are only glimpses and perhaps I’ll write a more rounded account of my experience of her one day; but for now, a celebration.

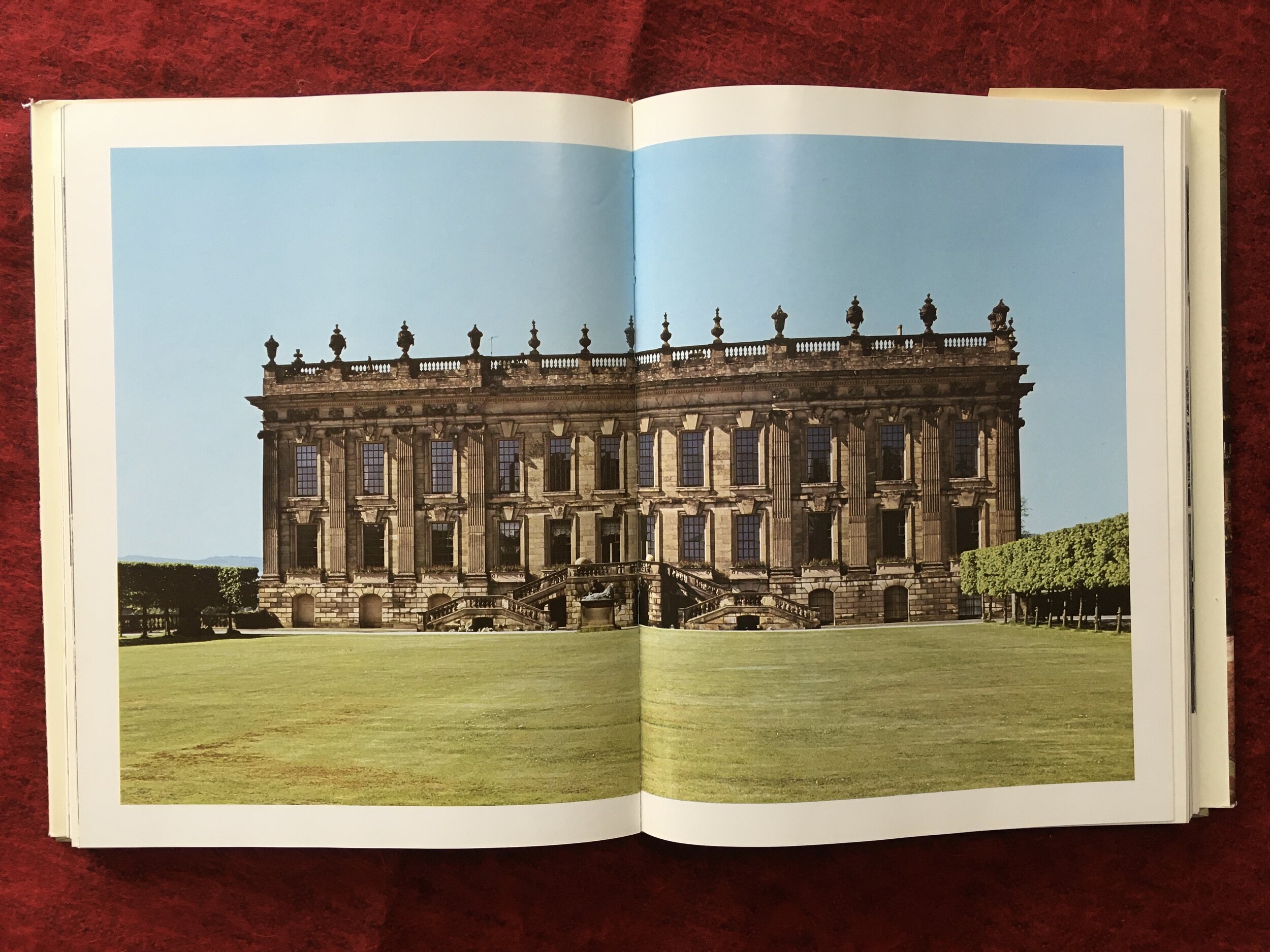

Photograph by John Bethell, from Nigel Nicholson’s 2nd edition of The Great Houses of Britain, 1978

When I was 12, believing I wanted to be an architect, I was given a book called ‘The Great Houses of Britain’. In it was a colour photograph (above) of a house I’d never heard of or seen, called Chatsworth. It captivated and mesmerised me, feeling oddly and intensely familiar, and soon afterwards I told anyone who’d listen that when I grew up, I was going to work in that house. I grew up in London, and had never been to Derbyshire, but from then on the county glowed with a strange allure on any map of England I looked at. I chose to write an ‘O’ level school project about Chatsworth, and that led to my first visit, with my father, aged 15. That was it.

Andrew and Deborah Devonshire at their golden wedding party, April 1991

10 years later, in the spring of 1991, with an art history degree under my belt, but little sense of what to do with it, I wrote to Debo from London, where I was unhappily temping at my girlfriend’s office, to ask her if I could ‘pick her brains’ about how to find work in the heritage industry in Derbyshire, a county I had fallen in love with from my repeated visits to Chatsworth. It was a ruse of course; I wanted to meet her, and I wanted to work at Chatsworth. I had one huge advantage; my godfather’s wife Joanna knew Debo and had warned her that she might get a letter from a young art history graduate in London who was a big fan. 48 hours later a handwritten response landed with me. ‘I don’t think we have anything for you here, but very happy to meet you if you could be this way at 11am on xx April’. Funnily enough, I could. We met, and I rabbited on about how much I loved Chatsworth and Derbyshire and her books and Lucian Freud and was planning to move north from London, and she watched and listened and asked pertinent, sympathetic questions, but made no promises or indeed suggestions. At the end of our hour, she said ‘Before you go, would you like to see the tent my husband is putting up in the garden?’

I couldn’t really imagine Andrew Devonshire putting up a tent and so I was intrigued. We put our coats on and headed outside, up a flight of steps and there, on the lawn, was the largest marquee I have ever seen, slowly being fitted out with tables and chairs, as far as the eye could see. This was the tent in which they were about to host a tea party to celebrate their Golden Wedding anniversary. Andrew had the idea of finding out how many couples in Derbyshire shared their marriage year and inviting them for tea, and it turns out that it was around a thousand. And so, as good as his word, the invitation was issued. I was there 48 hours before the party was due. As we walked through the tent, full of bustling catering staff, I watched Debo interact with them, and saw for the first (and I thought then for the last) time her particular version of what used to be called ‘noblesse oblige’. For everyone, she had a question about what they did, or what they were responsible for, always accompanied by appreciation and a word of encouragement, delight or amazement. What she was doing I realised, was creating a sense that she was in ‘cahoots’ with them, colleagues on a joint endeavour, rather than a grand Duchess issuing orders. I was to see her do this, to me and to many others, time and time again.

The Times later called the event, extensively covered in the papers and on TV, an example of the Duke’s ‘rampant paternalism’, and yes, it was a gesture from a former age, but it was also a not un-canny move by a couple who had, I later came to realise, over more than half a century managed to make Chatsworth feel like it belonged to all its visitors, that it was our backyard as much as their own.

I left on a high, having spent this one happy and revealing hour in Debo’s company, and assumed that was that. A few weeks later, I had a letter from the man who ran the house opening operation then, Eric Oliver; he ‘gathered’ from the Duchess I wanted some work experience, and he would be willing to offer me one of their ‘housemen’ summer jobs, largely to be spent cleaning visitor lavatories, chipping old mortar out of the water cascade and car parking. I said yes, and didn’t leave for 19 years.

Gordon Getty, Debo and myself at the Getty’s house in San Francisco, January 1999.

Within a few years of being at Chatsworth, I had started to give talks about the house, collections and garden, at first to school groups and teachers, then to other visitors and local societies, and I was eventually allowed out into the wider world to lecture and share my enthusiasm. This then led to speaking tours in America, sometimes in connection with exhibitions from Chatsworth’s collections, and otherwise hosted by the Royal Oak Foundation, whose lecture programme was supported by a friend of Debo’s, Drue Heinz.

The very best of these was in company with Debo, where we introduced each other’s lectures (though I remember with shame that my lecture in New York was the worst I’d ever given, under-prepared and badly delivered) and were treated, of course, like royalty – travelling with Drue and the Royal Oak director Damaris Horan, dinner with Jayne Wrightsman at 820 Fifth Avenue in New York, a tour of the new Getty Center in LA with its director John Walsh, tea at the wonderful Rose Tree Cottage, home of all things English, and then staying with Ann and Gordon Getty in their extraordinary house overlooking the Golden Gate bridge. Mr Getty hosted Debo’s lecture in his music room, where we both thought he had dozed throughout, but he was a very genial and sweet-natured host at the party afterwards. I jabbered on to Debo about the fact that my bathroom was hung entirely with original stage costume designs by Leon Bakst; she expressed her pity that poor old Mr Getty had had to sit through her ‘boring’ lecture.

Seeing her seduce her audiences in the US gave me a fresh perspective on Debo’s skill. In New York, she had stepped out onto the stage of the Metropolitan Museum, looked at the packed house over her half-moon specs, and begun, “Ladies and Gentlemen, it is quite a thing for an uneducated person like me to be speaking to what my father would have called ‘all the hot stuff in New York’.” Flattered and impressed, her audience would have laughed at her reciting her laundry list, let alone her lively lecture on what she called ‘the old dump’. When we got back to the UK, I wrote and thanked her for the experience and she wrote back with her thanks. ‘We certainly had an INNERESTING time, didn’t we’. Again, cahoots.

Two other memories of that trip. We were there during the Clinton Impeachment trial, and I was doubly fascinated became one of the President’s lawyers was also a Seligman (not a relation) and I was very much on her side at the time. Grounded by fog at Los Angeles airport, Debo and Drue asked me to see if I could find some newspapers and I returned with a batch of them. We all sat catching up on the latest gossip from the trial. Suddenly Debo lowered her paper and exclaimed, “Oh honestly, what do people think is going to happen. For as long as I can remember, any powerful, interesting man has behaved like this. What is all the fuss about?!” The frisson of course was that here was someone who had known JFK since he was 16, in London with his ambassador father, and who knew him well when President. She really did know what she was talking about, even if her views on the subject of philandering men were no longer quite the norm.

And my second memory was from before the trip began. We were going over the itinerary and I scoffed at the rather grandiose wording of the invitations to ‘join Her Grace the Duchess of Devonshire for a drinks reception’ and so on, and wondered if she wasn’t rather tired of such talk, and such events. “Not at all” she said. “Being a guest of honour is largely about listening to other people telling you their stories. It isn’t hard work to be interested, and I never have to say much at all. They will want to share their own experience of Chatsworth, or meeting one of my sisters, or some such and my job is to listen.” She was right, and I always remember her advice after I have given one of my own lectures. I am not in her league of course, either as a lecturer or as a public figure, but there are always people who want to come and tell me their story about Chatsworth, or about Debo or about some other aspect of Mitford or Devonshire family connections.

Debo and her friend Jayne Wrightsman at Chatsworth.

I found this photograph, uncredited, on the internet a few years ago, hence the poor quality. It shows Debo and Jayne Wrightsman, perhaps the most legendary of all the New York art philanthropists, no doubt in new dresses designed and made for them by their mutual friend Oscar de la Renta. I was lucky enough to meet Jayne a few times, at Chatsworth and then in New York when I was lecturing in the US, with or without Debo; dinner in her candlelit apartment, where you brushed past a pair of Canelettos just to get from the elevator to the hall, was especially fascinating; the people, the art, the food and the service of course, but also Jayne’s dry wit, range of cultural knowledge and the way in which she combined a beady eye with a gentle smile. After I’d give an afternoon lecture at the Met, which she kindly came to, no doubt at Debo’s behest, she came up onto the stage to find me in the wings and to thank me. She very slightly inclined her head towards me, and it dawned on me that this was a sign that I should proffer a kiss on her cheek. I felt as though I was suddenly being intimate with the Sphinx.

Every summer, in the late 1990s, as Debo relates in her memoir, she and Andrew would host a weekend for their American friends at Chatsworth, centred on Jayne but also usually involving the de la Rentas, and other variations of guests. On one Sunday morning, when I was duty manager for the house opening, Debo called and asked if I could spare a moment and come up to the drawing room. I headed up, and there, once I had bumped past Barbara Walters, hard to recognise under a baseball cap, and been greeted warmly by Jayne, I found Debo surrounded by other guests. “Now Simon, could you take Mr Kissinger around the visitor route and then bring him back for lunch?” Too surprised to say I was too busy with duty manager tasks, I shook hands with the gravel voiced Kissinger, and we headed off around the house. After we’d been through a number of rooms, I started to develop an anxiety that he was being gently hissed; I was sure I could hear it. I couldn’t imagine that Chatsworth’s visitors that day had particularly strong views on my not-uncontroversial tour guest, but perhaps they were a more politically minded bunch than I thought. I conferred briefly with a colleague, one of the room stewards. “No no” he said, “it’s not hissing, but they are all whispering ‘Is that Henry Kissinger’”. The man himself said almost nothing throughout, and didn’t so much as turn around to acknowledge me when I led him back to their pre-lunch drinks. In my entire 19 years at Chatsworth, it was one of the very few times I felt taken for granted.

Image by David Vintiner.

The Chiswick parterre at Chatsworth

To my mind, of all the things Debo added to the garden at Chatsworth, this was both the most original and in its own way, the most subtle. The idea for it came when she was looking at architectural plans of Chiswick Villa in London, once a Devonshire family home having been inherited by marriage when the daughter of its builder, Lord Burlington, married the future 4th Duke of Devonshire. Debo noticed that the central dome on the plan was about the same size as the pond in a square section of the private garden at Chatsworth that she wished to change. With more than 3000 box hedge plants, she had the entire floor plan of Lord Burlington’s Chiswick laid out around the pond, thus paying homage to the great 18th century patron and collector, whose rich collections and library so enhance Chatsworth to this day. I’ve never seen such a garden, before or since, where architecture became plants, and I liked the conceit; the ghostly echo of another treasure house, long since sold, but also evoking memories of the ornate box parterres that had surrounded Chatsworth in the late 17th century. Debo was often acutely (and perhaps wilfully) a-historical, but here she had found exactly the right balance; it felt both modern and deeply respectful of the past, and never looked better than in the snow. It has gone now, swept away under the rigorous eye of the brilliant architect Peter Inskip, who led the team who undertook the vast Masterplan instigated by Debo’s son in the early C21st; both Peter and the Duke felt it was out of place; for once, I think they were wrong, but it was their garden, not mine!

A moment at our wedding

Debo came to our wedding, which we held in the garden of the estate house we lived in as part of the job, an extraordinary place a mile up a track, with no traffic, surrounded by sheep meadows and with a stream running through the garden. It had been due a thorough update when she offered it to us (‘I don’t suppose you and Sophie would ever like to live up a track in a big old house with a garden and no neighbours’, she had wondered one day.) and so we had the unbelievable good fortune to influence how the work was done, and get it decorated to our specification.

When it came to the wedding, we committed a terrible etiquette faux pas. I addressed the invitation to her alone, thinking that the Duke, pretty unstable on his feet by this time, would never want to come to a ceremony being held on a steep grass slope, but when she rang to thank me and accept, she said, very pointedly, ‘The Duke and I are both delighted to have been invited, but I don’t think he’d be able to manage the sloping grass, so I will come on my own’. It had been thoughtless of me; I didn’t mind breaking the etiquette so much, but I was soon to discover that he was much more mindful of my work at Chatsworth than I had ever known. When, 18 months later, a crisis unfolded within my family, which involved 6 weeks of intense worry over someone who had gone missing, he was - they both were - very concerned for me. After it was over, he asked to see me, to say – in another example of his ‘rampant paternalism’ - that he’d like to take on responsibility for sorting out the situation my family found ourselves in, and wanted to help with money, advice, etc. It was not appropriate, or realistic of him, but it was offered in a spirit of common humanity and I was very touched.

Sophie and I had first met at Chatsworth and had taken many walks together through the garden along Paxton’s little stream when we were getting closer, and here we were getting married in this idyllic Chatsworth valley; it was important to me that Debo, who had really watched me grow from boy to man, nudging me along the way, should be there. And when our first daughter was born 15 months later, I was woken the next morning by an early knock on the door. A member of the garden team was standing there, with a basket containing two bunches of the Muscat grapes they grew in the greenhouse, a gift for mother and baby from Debo. They are the most delicious grapes we’ve ever tasted.

Image believed to be by Bridget Flemming

The millennium ball at Chatsworth

Debo and Andrew’s 80th birthdays, and their 50th year as Duke and Duchess, fell in the Millennium year 2000. They decided, you may not be surprised to read, to throw two parties; one night a fancy dress party for everyone who did or had worked for them over the previous 50 years, and the following night, a black tie dinner for everyone who had held civic office in Derbyshire in those five decades. Debo brought out of storage the 1897 dress made by Worth of Paris for a previous Duchess (when she’d hosted the Devonshire House ball in London for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897), and topped it with the bigger of the two family tiaras augmented with pearls and feathers. At some point I rocked up in my sleazy 1970s blue suit and shaggy wig, with my wife Sophie by my side. Debo looked us over; ‘Sophie looks lovely; you look like a disgusting queer girl’. I was suitably pleased. This photo was taken a few moments later; I am behind her, greeting Duke Andrew; Debo is expressing her delight at the Elvis costume another guest had rocked up in.

With Sophie, Debo and other guests at the farewell dinner

Farewell dinner at Chatsworth, May 2010

In March 2010, I resigned from my job as Head of Communications at Chatsworth. I had done what I could with the job, it needed now to be done by someone with a passion for targets and spreadsheets and the science of marketing, which held no interest for me. And it was time to become my own master and see what might happen next. By coincidence, another Chatsworth manager resigned in the same week to head to a new job, and a few days later we both received a wonderful call from the Duke. ‘Would we,’ he wondered, ‘fancy sharing a farewell dinner in the Great Dining Room? We’ll invite my mother and your managers and then you can each invite 15 guests of your own’. On the whole, we thought we would.

50 people gathered in that incredible room, and there was a little one-use camera on every chair, so hundreds of photographs were taken that night, each from a different vantage point. It was a final act of incredible generosity towards me (and my colleague) from the Devonshires, and it passed in a kind of giddy dream. In my speech, among my many thank yous, I thanked Debo for believing in me before I had ever believed in myself, and for the laughter and fun we had shared. But what I also wanted to say, and chose to say to her privately, was how much I had valued her rigour and her forthrightness. When I had gone to tell her I was resigning, without a new job to go to, her first question was exactly the one I needed asking. ‘Would it be very rude to ask how you propose to make a living?’ No, not rude Debo, just painfully to the point. As always.

Debo at 90 – proud and resigned

This photograph was taken almost exactly10 years ago, snapped by a Yorkshire Post photographer as we were preparing for a television interview, in anticipation of her 90th birthday and a celebratory exhibition that was opening in the house.

This was just about the last media work I supported her with, and it was complicated. She had decided she wouldn’t like some of the changes that her son and daughter in law were making to the visitor route, changes of display and layout, which other disgruntled old timers were no doubt telling her about, but which she had not actually seen for herself. The photographer was desperate to get her into one of the newly laid-out state rooms, where the light was perfect for the shot. ‘Absolutely not’ said Debo. ‘In here (the exhibition) or not at all’. It was exasperating, and I had to negotiate our way through, so that she remained in good form for the interview, which went off OK. But I think I understood what was going on.

For her, the changes to the place that had been her absolute domain for 54 years were just too close to the bone; the downside of becoming so closely identified with every stone and blade of grass, both in her own mind and in that of staff and visitors, was that any change must have felt like a very personal intrusion. I wished she could have risen above it more, and been as thrilled as I was that the next generation were as deeply engaged by Chatsworth’s magic as she had been, but she was 90 and proud and it was all too much change. That meant staff members like me who felt great loyalty to her personally, but an equal professional loyalty to our jobs and to her son and daughter in law, had a delicate balancing act to perform.

Later that year, after I had left my job and had no conflict of interest to manage, I interviewed her on stage at the Cheltenham Festival, about her memoir and her life. We discussed what I should call her when on stage. ‘Do you think it might be time for you to call me Debo?’ Again, I saw the magic she exerted on an audience. The queue for the book signing afterwards was twice as long as that for Howard Jacobson at the next table. I wondered idly what would have happened if they had met and talked, perhaps about her sister Diana Mosley. Worlds apart.

During the interview, she had occasionally stumbled for words and my questions had been designed to prompt the memories that didn’t come quite so fast. Little did I realise that within a year or so, she would be in the grip of a dementia so unrelenting that she barely knew anyone. The light had gone out.

Elisabeth Frink’s ‘Leonardo’s Puppy’

This was Debo’s favourite Frink sculpture (she had known the artist and been involved in the acquisition of a number of works) and it was placed outside the front door of her final home, where she would pat its head gently as she came or went. After her death in the Autumn of 2014, her funeral was the last great gathering of her tribe, attended by thousands. She didn’t let them down, and during the service, in which her name was not mentioned once, on her express orders, we listened to Elvis singing ‘How great thou art’.

One of the people at the wake was Mary Fry, co-owner of Rose Tree Cottage, the English tea room and shop in California that Debo and I had visited on our lecture trip so many years before. Mary had come over specially for the funeral and we reminisced together. A week later, who should walk into her tearoom for some shopping but Elvis's widow, Priscilla, so Mary broke her strict rule of not invading the privacy of her customers and told her about the English Duchess and her infatuation with her husband and his music, bringing a tear to Priscilla’s eye.

The Frink puppy came to Chatsworth; these are two photographs I took of it one summer, watching quietly over the house that has flowered in new and wondrous ways on the foundations that Debo and her husband laid down over 54 years. If you seek a monument to her, it seems to say, look around you.

Thank you Debo.

Text copyright Simon Seligman 2020